By Dr Paliani Chinguwo (PhD), Lost History Foundation.

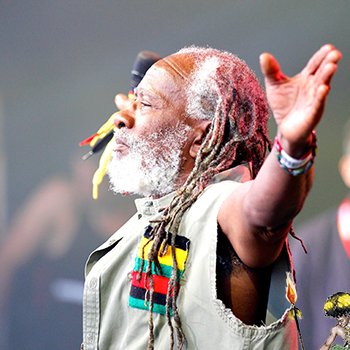

As Malawi hosts the legendary reggae artist Burning Spear this week, we delve into the untold history of reggae music in the country.

Context

From 1966 to 1993, Malawi operated as an authoritarian and one-party state under the Life President Dr. Kamuzu Banda. Among others, this period was marked by stringent censorship that negatively affected the dissemination of both academic materials and entertainment content, including music.

Though the state controlled Malawi Broadcasting Corporation (MBC) radio allowed some reggae music to be aired, any music containing overt political messages or sentiments that could be interpreted as resistance against the authorities was strictly banned. Songs such as “I Shot the Sheriff” and “Burning & Looting” by Bob Marley; “Fite Dem Back” or “All We Doin is Defendin” by Linton Kwesi; and “I Want to Be Free” by I Jah Man Levi were considered politically not suitable for the Malawian audience.

For reggae fans, accessing this genre of music became a significant challenge during this era. This is where the story of an unlikely reggae distributor, a lecturer of psychology at the University of Malawi, comes in.

Enter Prof. Stephen Edward Buggie

Prof. Stephen Edward Buggie was born on 27 August 1946 in Minneapolis, USA. He obtained his Master of Arts (MA) and doctoral (PhD) degrees in psychology from the University of Oregon in 1970 and 1974 respectively. In 1980, he moved from the University of Zambia to join the University of Malawi where he became the founding head of the Psychology Department at Chancellor College in Zomba.

However, Prof. Buggie’s activities in Malawi as a scholar were not confined to the lecture rooms. His arrival coincided with a time when reggae music had taken root in other parts of Africa but was still struggling to find a foothold in Malawi due to the rigid control of media by the state. Despite the censorship on MBC radio and the absence of local stores selling the latest reggae records, Prof. Buggie became a pivotal figure in Malawi’s underground reggae network.

During an interview, Ras Chivomelezi (aka Earthquake) disclosed, “In the late 1980s, I lived in Ndirande township (Blantyre), but I often spent school holidays with my cousins in Zomba. Every time I visited, I found them listening to politically and spiritually charged reggae music that was never played on MBC radio. Most of the reggae albums and artists were introduced to me through my cousins. They sourced this reggae music from Prof. Buggie.”

Unofficial Reggae Distributor

Prof. Buggie became a go-to source for those seeking the latest reggae albums in the 1980s. Having access to reggae music from abroad, he reproduced and distributed reggae music on radio cassettes. He was known to fulfill requests from reggae fans not only in Zomba, where Chancellor College was located, but also in Blantyre, Lilongwe, Ntcheu, Mzimba, and beyond. People sent blank cassettes to him, and he would record the requested songs/albums, label the tapes, and return them at a minimal fee.

Even students at secondary schools in Zomba and beyond found ways to tap into this underground reggae music network. Some of the students subscribed to Pentecostal churches in the USA and Europe, from which they would receive cassette tapes of prayer sermons. These cassettes were then repurposed by sending them to Prof. Buggie, who replaced the sermons with reggae music, effectively creating a covert means of distributing some of the reggae tunes that the one party state had sought to keep under control.

“I attended Ntcheu Secondary School from 1984 to 1988. I discovered a network of reggae enthusiasts connected to Prof. Buggie in Zomba, which I immediately joined. Before the school holidays, we would give blank tapes (sometimes tapes we received from churches abroad) to fellow students heading back to Zomba, who would take them to Prof. Buggie. For a minimal fee, he would record the reggae music we requested. When school reopened, the students from Zomba would bring us the tapes filled with the reggae tracks. Prof. Buggie could source any kind of reggae music you wanted,” remarked Peter Makaula during an interview.

A Rebel with a Cause

Prof. Buggie’s distribution of reggae music was just one aspect of his quiet defiance against the limitations posed by the state. His access to international news, particularly through recorded television (TV) bulletins from the USA, added another layer to his activism. At Chancellor College, Prof. Buggie would show recorded news from TV networks like ABC, during lunch hour to students and staff.

In the absence of TV station in the country, these recorded broadcasts provided information about world events that were often censored or not covered on MBC radio.

One of the most significant recorded TV broadcasts that Prof. Buggie beamed at Chancellor College, was the coverage of the student-led demonstrations in Beijing at Tiananmen Square. The protests, which began in April 1989, captured the world’s attention.

In Malawi, the coverage was deemed too politically sensitive for the general public. By showing these news clips, Prof. Buggie allowed students and staff at Chancellor College to witness a historic act of defiance, one that drew uncomfortable parallels with Malawi’s own political climate. This bold act did not sit well with the authorities such that it is alleged this was the reason he was immediately deported.

Aftermath

In the wake of the transition from a one-party state to multi-party democracy in 1993, MBC radio began airing reggae music more freely. The launch of the ‘Reggae Sundown’ program with Chaipa Hiwa marked a turning point. The show allowed Malawians to enjoy the genre without the same level of censorship that had characterized the previous era.

As soon as Chaipa Hiwa left for South Africa in 1994, Geoffrey Kazembe assumed control of the reggae show and renamed it ‘Sundown Reggae’. While Prof. Buggie was no longer in the country by this time, the seeds he planted had already taken root.

Conclusion

The history of reggae in Malawi is not just about music: it is about resistance and the struggle for freedom. Figures like Prof. Buggie, though unconventional, played a crucial role in ensuring that the fire of reggae music—and the core political and spiritual messages it carried—continued to burn, even in the face of censorship.

Today, Malawi’s vibrant reggae scene owes much to the quiet rebellion of those who kept the music alive when the state tried to suppress it.

NB: More details in a book by the Lost History Foundation (LHF) coming out soon on the History of Reggae Music in Malawi.